- DNS first. Always. Check it before you blame anything else.

- Ping the gateway before touching a single config file.

- Learn /24 and you're set for 90% of cases. Seriously.

- Memorize three private ranges: 10.x, 172.16-31.x, 192.168.x. That's the whole list.

- Work up the stack: cable, gateway, DNS, port. In that order, every time.

💡 Priority #1 is not optional. I've watched people spend hours reconfiguring firewall rules when the DNS server was just down. Hours.

Here's the entire field of networking in one sentence: get a packet from one machine to another. That's it. Every protocol, every acronym, every piece of hardware exists to solve some version of that problem. Addresses tell you where. Routes tell you how. DNS tells you who. The rest is plumbing.

What makes it confusing isn't that any single concept is hard. It's that ten simple concepts stack on top of each other, and when something breaks at layer two, the symptoms show up at layer seven. So you end up debugging your web app when the actual problem is a bad cable.

IP Addresses Explained

Four numbers. Dots between them. 192.168.1.100. Each number ranges from 0 to 255.

That gives roughly 4.3 billion combinations, which sounded like plenty in 1981 and is nowhere near enough now. IPv6 fixes this with absurdly long addresses, but for homelab and internal work, you'll almost exclusively deal with IPv4. We'll stay there.

Private vs Public Addresses

Three ranges are carved out for internal use. Burn these into memory:

10.0.0.0to10.255.255.255172.16.0.0to172.31.255.255192.168.0.0to192.168.255.255

None of these are routable on the public internet. They exist only inside your network. Your ISP gives you one public IP, and your router performs NAT — Network Address Translation — to let every device in your house share that single address.

Your phone wants to load a webpage. It sends the request from 192.168.1.50 to the router. The router swaps that private address for your public one, say 73.45.231.15, and sends the request out. When the response comes back, the router remembers which internal device asked and forwards it to the right place. Elegant, if slightly hacky.

Subnet Masks: What the /24 Means

You'll see notation like 192.168.1.0/24 everywhere. The number after the slash is the subnet mask, and it confused me for an embarrassingly long time.

What it means: the /24 says "the first 24 bits of this address identify the network." The remaining 8 bits identify individual devices on that network. In plain terms, the first three numbers are the neighborhood, and the last number is the house.

192.168.1.0/24 breaks down like this:

- Network: 192.168.1.x

- Available hosts: 192.168.1.1 through 192.168.1.254

- 254 usable addresses total — .0 is reserved for the network itself, .255 is broadcast

Common Subnet Sizes

| CIDR | Subnet Mask | Usable Hosts | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| /24 | 255.255.255.0 | 254 | Home networks, homelabs, small offices — the default for a reason |

| /25 | 255.255.255.128 | 126 | When you want to split a /24 in half for VLANs |

| /16 | 255.255.0.0 | 65,534 | Corporate networks, cloud VPCs |

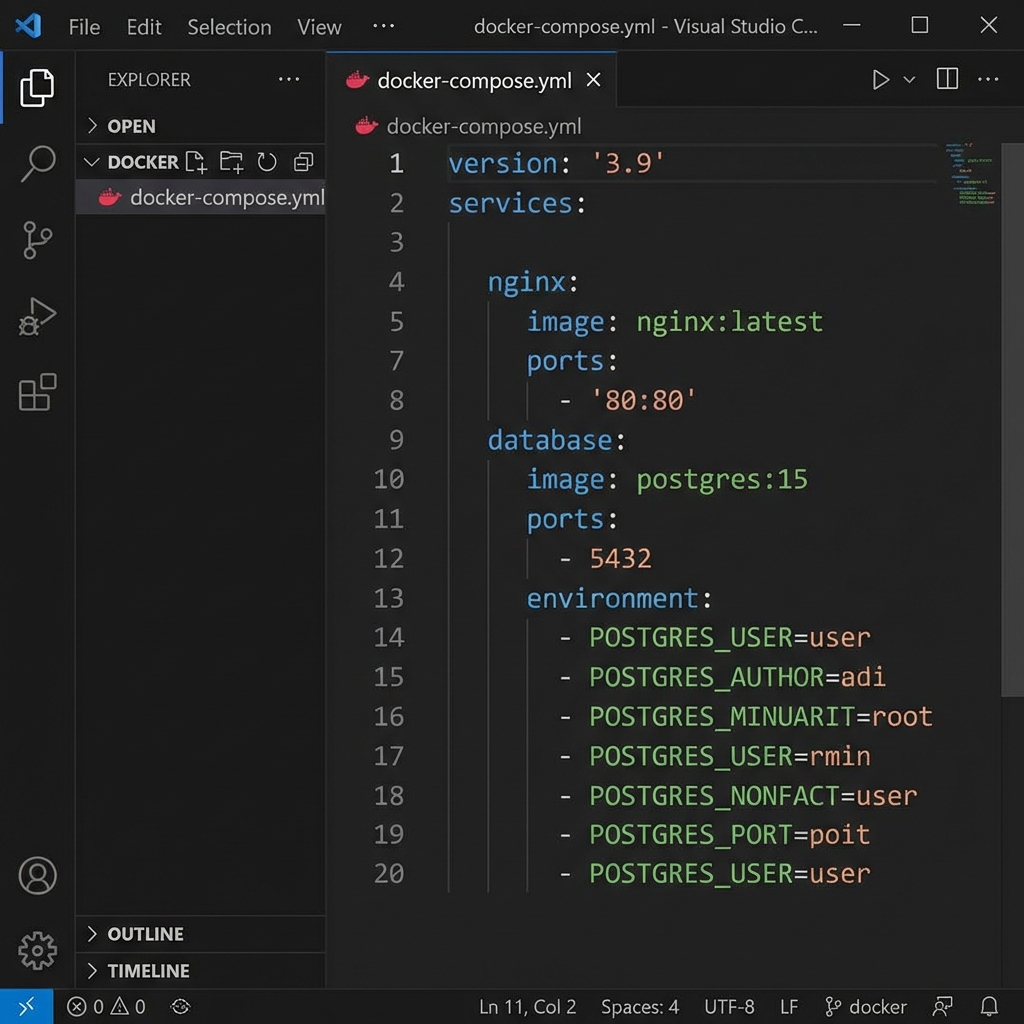

Use /24. For your homelab, for your Docker networks, for basically everything. I've seen people create elaborate subnetting schemes for a five-device home network. Don't.

How Devices Find Each Other

Same Network (Direct Communication)

Two devices on the same subnet talk directly. No router involved. Device A broadcasts an ARP request — "Hey, who has 192.168.1.50?" — and Device B answers with its MAC address. After that exchange, they send frames directly to each other. Fast. Simple.

Different Networks (Routing)

Different subnet? The packet has to go through a router. Your machine checks the destination IP, realizes it's not local, and sends the packet to its default gateway instead. The gateway — usually 192.168.1.1 on home networks — figures out where to forward it next.

If your default gateway is wrong or missing, nothing outside your local subnet works. This is the second most common misconfiguration I see, right after DNS.

DNS: The Internet's Phone Book

This section is intentionally the longest in the guide because DNS causes more real-world outages than everything else on this page combined. I'm not exaggerating. In five years of managing infrastructure, probably 60% of "the network is down" tickets turned out to be DNS.

The basic idea: nobody types 142.250.80.46 into a browser. You type google.com, and something has to translate that name into an IP address before any connection happens. That something is DNS.

The lookup chain goes like this:

- Your browser checks its own cache. Already resolved this domain recently? Use that.

- Cache miss. Ask the OS resolver, which checks

/etc/resolv.confon Linux to find which DNS server to query. - The configured DNS server — maybe 8.8.8.8, maybe your router, maybe a Pi-hole — either has the answer cached or goes through a recursive lookup: root servers, then TLD servers, then the authoritative nameserver for that domain.

- Answer comes back. Browser gets the IP. Connection proceeds.

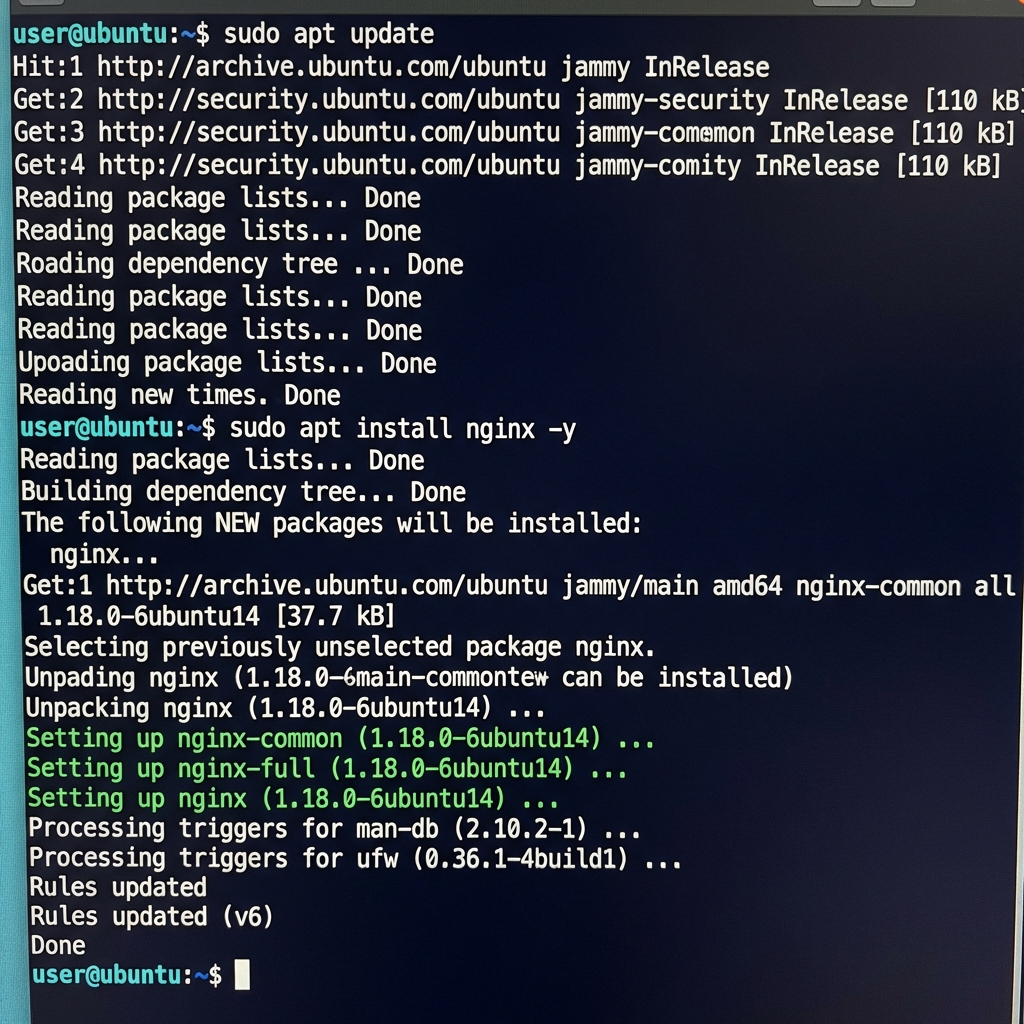

All of that happens in milliseconds. Usually. When it doesn't, everything stalls. Web pages won't load. APIs time out. Docker containers can't pull images. apt update fails. And the error messages almost never say "DNS failure" — they say "connection timed out" or "could not resolve host" if you're lucky, or just hang silently if you're not.

Here's what catches people: you can have perfect network connectivity and still be completely broken if DNS is down. ping 8.8.8.8 works. ping google.com doesn't. That gap is DNS, every single time.

The other thing that bites people is DNS caching. You update a DNS record, but the old IP is cached at multiple levels — your browser, your OS, your upstream resolver. TTL values control how long caches hold records, but some resolvers ignore TTL entirely. I've waited hours for changes to propagate when the TTL was set to 300 seconds. Flushing your local cache helps, but it only fixes one layer.

Testing DNS

# Look up a domain

nslookup google.com

# Or with dig (more detailed)

dig google.com

# Test a specific DNS server

dig @8.8.8.8 google.com

# Check what your system is actually using

cat /etc/resolv.conf

# Flush DNS cache on Linux (systemd-resolved)

sudo systemd-resolve --flush-caches

# Flush on macOS

sudo dscacheutil -flushcache; sudo killall -HUP mDNSResponderMy troubleshooting habit: if something network-related breaks, I run dig before I do anything else. Takes two seconds. Saves twenty minutes of chasing the wrong problem. If dig @8.8.8.8 example.com works but dig example.com doesn't, your local DNS server or config is the issue. If neither works, the problem is upstream or the domain itself.

One more thing. If you run containers, each container typically gets its own DNS resolution config. Docker uses 127.0.0.11 as an embedded DNS server. Kubernetes has CoreDNS. When a container can't resolve hostnames but the host machine can, check the container's /etc/resolv.conf — it's almost certainly pointing somewhere different than you expect.

Ports: Addressing Applications

IP gets you to the machine. Port gets you to the application running on it. Think of the IP as the building address and the port as the apartment number.

The ports you'll actually encounter:

22- SSH80- HTTP443- HTTPS53- DNS3306- MySQL5432- PostgreSQL

Notation like 192.168.1.100:8080 means "port 8080 on that machine." Your browser, when connecting to a web server, picks a random high-numbered port on your end and reaches out to 443 on the server's end. You never see your side's port number unless you're looking at packet captures or netstat output.

Checking Port Connectivity

# Quick check — is something listening on this port?

nc -zv 192.168.1.100 80

# Telnet works too (old school but reliable)

telnet 192.168.1.100 80

# PowerShell on Windows

Test-NetConnection -ComputerName 192.168.1.100 -Port 80DHCP: Automatic IP Assignment

Plug a device into a network and it doesn't magically have an address. It broadcasts a DHCP request — basically shouting "someone give me an IP." A DHCP server, usually your router, responds with an available address plus the gateway and DNS server to use.

Device: "I need an IP."

DHCP Server: "Take 192.168.1.50. Gateway is 192.168.1.1. DNS is 8.8.8.8. Lease expires in 24 hours."

That lease part matters. DHCP addresses aren't permanent. They expire and get renewed. For most client devices — laptops, phones — this is fine. For servers, you want static IPs, configured manually, so the address never changes. Imagine your database server quietly getting a new IP because the DHCP lease expired. Chaos.

Key Troubleshooting Commands

Check Your Own IP

# Linux (modern)

ip addr

# Linux (legacy) or macOS

ifconfig

# Windows

ipconfigARP. Every networking guide treats it like a footnote — "ARP resolves IPs to MAC addresses" — and moves on. But when you actually run into an ARP problem, you're completely lost because nobody ever told you how ARP tables work, what ARP cache poisoning looks like, or why two machines on the same switch can't talk to each other despite having correct IPs. I've seen stale ARP entries cause intermittent connectivity issues that lasted weeks because nobody thought to check arp -a. It's not glamorous. It's not a fun topic for a blog post. But the gap between "I've heard of ARP" and "I can troubleshoot ARP" is where real network debugging skill lives, and most guides don't bother bridging it.

📝 Quick note: If ping 8.8.8.8 works but your browser can't load anything, stop. It's DNS. Don't go further until you've confirmed that.

Test Basic Connectivity

# Step 1: Can I reach my gateway?

ping 192.168.1.1

# Step 2: Can I reach something on the internet by IP?

ping 8.8.8.8

# Step 3: Can I resolve a hostname?

ping google.comRun these in order. Step 1 fails? Local network problem — cable, VLAN, switch. Step 2 fails but 1 works? Routing or firewall. Step 3 fails but 2 works? DNS, full stop.

Trace the Route

# Linux/macOS

traceroute google.com

# Windows

tracert google.comThis shows every router between you and the destination. When packets are dying somewhere in the middle — reaching your ISP but not beyond, or making it to a CDN edge but timing out — traceroute tells you exactly which hop is the problem. Honestly underused.

Check What's Listening

# Linux

ss -tuln

# macOS

netstat -an | grep LISTEN

# Windows

netstat -an | findstr LISTENINGThis answers the question "is my application actually listening on the port I think it is?" You'd be surprised how often the answer is no.

The Layered Model (Quick Version)

Seven layers in the OSI model. I use three of them regularly. Maybe four. The "session layer" and "presentation layer" are concepts I've never needed outside of a certification exam. Here are the ones that matter for real troubleshooting:

- Physical (1) - Is the cable plugged in? Is the link light on? Laugh all you want, I've spent 45 minutes debugging a "network outage" that was a loose ethernet cable.

- Data Link (2) - MAC addresses, switches. The layer where ARP lives.

- Network (3) - IP addresses, routing. Can I ping it?

- Transport (4) - TCP/UDP, port numbers. Is the port open?

- Application (7) - HTTP, DNS, SSH. Is the service actually responding correctly?

Troubleshoot bottom-up. Always. Start at the physical layer and work your way to application. Skipping ahead is how you waste time.

Quick TCP vs UDP

TCP: reliable, ordered, slower. Used for web, SSH, file transfers. UDP: fast, no guarantees, fire-and-forget. Used for DNS, streaming, gaming. That's it. You don't need more than that unless you're writing socket code.

VPNs and Tunneling

A VPN wraps your traffic in an encrypted tunnel. Your packets enter the tunnel on your device, travel across the internet in encrypted form, and emerge on the VPN server's end. From your machine's perspective, you're on the remote network. You get an IP on that network. You can reach internal resources as if you were sitting in the same building.

Practical uses: accessing your homelab from a coffee shop, connecting to a corporate network from home, or routing all your traffic through a trusted exit point when you're on sketchy public wifi. WireGuard has made self-hosting a VPN almost trivially easy compared to the OpenVPN days.

Firewalls in Two Sentences

A firewall is a list of rules. "Allow port 22 from 10.0.0.0/8. Drop everything else." That's essentially all it does.

The catch: there are usually multiple firewalls between you and your destination. The host firewall (iptables, ufw, Windows Defender). The router's firewall. Cloud security groups. Any one of them can silently drop your packets with zero feedback. When a connection just hangs — no error, no rejection, just nothing — a firewall is almost always silently discarding the traffic.

Real Troubleshooting Workflow

This is the actual sequence I follow. Every time. No shortcuts.

- Do I have an IP? -

ip addr— if not, DHCP or cable issue - Can I hit the gateway? -

ping 192.168.1.1 - Can I hit the internet by IP? -

ping 8.8.8.8 - Does DNS resolve? -

dig google.com - Can I reach the target machine? -

ping TARGET_IP - Is the target port open? -

nc -zv TARGET_IP PORT - Is the application running? - check logs on the target

Steps 1 through 3 take thirty seconds. They tell you whether the problem is on your side, in the middle, or on the remote end. Most people skip straight to step 7 and waste time reading application logs when the issue is a gateway misconfiguration two layers below.

What's Next

Where to go from here depends on what you're building:

- VLANs — segment your homelab into isolated networks. The natural next step if you're running multiple services.

- NAT internals — port forwarding, hairpin NAT, the stuff that matters once you expose services to the internet.

- IPv6 — allegedly the future. It has been "the future" for fifteen years. But it's showing up in more places now and worth knowing.

Honestly, most networking problems come down to three things: wrong subnet, wrong gateway, wrong DNS. Fix those and—

💬 Comments